* Warning: Intellectual stuff! - jump altogether if you are not into psychology and deconstruction.

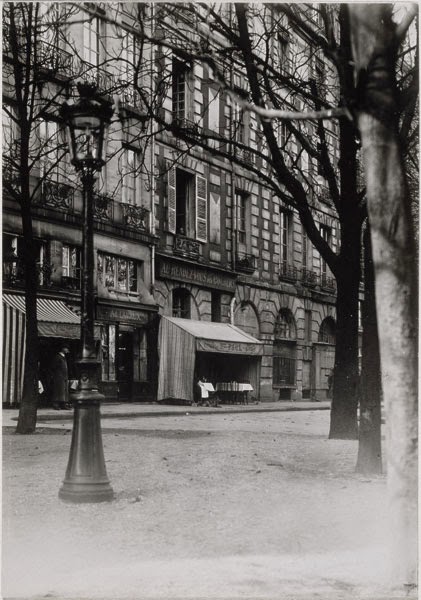

My friend Daniel Jouanisson, videographer, sent me this photo update on the squares of Paris in 'Nadja'. Judge yourself how little they have changed in almost one century!

My friend Daniel Jouanisson, videographer, sent me this photo update on the squares of Paris in 'Nadja'. Judge yourself how little they have changed in almost one century!

|

| Hotel des Grands Hommes |

How important were those squares for the the story of Nadja? Here is another interpretation by Critic David Bate, from Westminster University in 'Photography and Surrealism' .

Deconstruction technique is interesting here because it allows to get to the bottom of the most indifferent image, and extract its true meanings. Remember: no photograph is innocent!

You can always connect it to a context, to a choice and a photographer's point of view. Here we are told about Nadja's madness, so pychanalysis is suitable, and it might even explain the hidden meaning of those sad squares that populate the book.

In his book, Bate relates Surrealism and Sexuality, giving an explanation to the Enigmatic.

Some images draw us, even if we don't know why. Interpretation can provide the explanation. Finding the culprit is like finding a serial killer by Forensic Science.

Out of necessity the language is specialized. My comments will try to clarify.

David Bate: "The photographs in 'Nadja' echo this structure of loss through their emptiness. As the reader views the photographs in relation to the text, the pictures are dis turbingly empty, 'lacking' in actual events. Looking into these photographic spaces where any decisive momenthas 'disappeared', we wonder what is the other there.

Just as Nadja loses her image of identification, so the

reader of Nadja is deprived of a reflected identification

in the photographs. Most of the photographs, even the

portraits, have a mute and mournful look, there is a

'dinginess' in these pictures, rarely noted by commenta-

tors as such, through which their 'mood' of emptiness

invades the book.

Expecting to find photographs of the events in their captions, the reader finds them lacking and it is in this way that an enigma emerges".

In the book the onset of the Enigma is also marked by the impromptu appearance of a fortune teller:

|

When Nadja told Breton she saw herself as Helene, Breton was reminded that a clairvoyant had predicted days before their meeting that he would get involved with a Helene. Another unlikely coincidence!

Breton and Nadja are approaching the Unconscious zone, which is timeless. They can meet, but they can also differ, having different unconscious goals.

David Bate: "Towards the end of Nadja, Breton says that he wanted some of the photographic images of the places and people to be taken 'at the special angle from which I

myself had looked at them'. This proved impossible;

the places 'resisted' this and thus, for Breton, 'as I see

it, with some exceptions the illustrated parts of Nadja

are inadequate'

"Breton mythologizes these places, as having some-

thing in them which resists representation. This only

makes those places gain in enigma. There is little or no

attempt to show things as literally from Breton's point-

of-view in the photographs. In the photograph of Place

Dauphine, the view is outside, looking in. One would

have to be a disembodied voyeur to be able to 'see' what

cannot be seen in these photographs. Whatever Breton

says himself in the book, the photographs make crucial

contributions and their presence gives a distinct feeling

to the book. Can it be that this is what Breton meant

when he described the photograph as 'permeated with

What is not said is that most of those somber Paris' squares in fact have been the theatre of acts of blood. In Place Dauphine was executed Jaques de Molay, the Master of the Knights Templar. Nadja perceives it and exclaims: "Et les Morts, les morts!" - she can feel the dead, she registers them. She predicts a black window turning red, and a few instants later a window lights up showing bloody red curtains!

Another of those squares they meet at is where Marie Antoinette was beheaded. Those are not innocent places. They carry the mark of the public execution of a paternal figure.

"'Sadness', says Julia Kristeva,'is the fundamental mood

of depression.' Certainly the photographs in Nadja are

not joyous, they resonate with solitude. The ghosts of

'whom I haunt' appear through their absence; as in the

solitude of the child at the primal scene, with the parents

'away' enjoying themselves. In this paradoxical signifying

structure the signs are empty but never 'empty', they

still signify. The enigmatic message of emptiness draws

us back to those feelings and affects in the story of

Nadja, where madness and sanity are combined in

the mood of melancholy sadness. This mood is based

on an identification with the lost object, where the

depressing and depressed feelings hide an aggression

against that object." [The Father Figure, she identifies Breton with]

"Nadja is a story in which Breton nevertheless undoes

himself a little. He is clearly haunted by Nadja's 'madness'

and the experience of their encounter — even if, as a

trained psychiatric nurse, he can still say: 'You are not

an enigma for me.'

"Meanwhile, the eyes of Nadja,repeated insistently

in Man Ray's montage of them in Nadja,

place Breton and the reader under her surveillance

(an image added by the author in 1964)."

"Meanwhile, the eyes of Nadja,repeated insistently

in Man Ray's montage of them in Nadja,

place Breton and the reader under her surveillance

(an image added by the author in 1964)."

"The book ends famously with the seemingly im-

promptu and rushed conclusion: 'Beauty will be CON-

VULSIVE or will not be.'The 'beauty' here for Breton is

the hysteric in convulsion, but in the end, Breton remains

on this side of the symbolic order, he is the neurotic

witness to his own unconscious conflicts, while Nadja

is given to signify the unconscious and can no longer

bear witness to her own thoughts.

"Nadja transgresses the symbolic order and pays the price of incarceration. As Simone de Beauvoir wryly notes: 'She is so wonderfully liberated from regard for appearances that she scorns reason and the laws: she winds up in an asylum.'"

"Nadja transgresses the symbolic order and pays the price of incarceration. As Simone de Beauvoir wryly notes: 'She is so wonderfully liberated from regard for appearances that she scorns reason and the laws: she winds up in an asylum.'"

"The paths of the sexual question 'Who am I?' are

different for the man and the woman in 'Nadja'. The

different trajectories relate to the different relations to a

paternal image. If beauty is hysteria, it is in the opening

up of an identification with the other. In patriarchal

law, as Lacan points out, the question of 'woman' is of

an 'identification with the paternal object' through the

Oedipus complex. It is surely this relation that Breton

explores in Nadja and is perhaps why the photographs he

chooses are so emptied of such potential identifications,

except one photograph: of himself. "

To Nadja the acts of blood make the squares terrifying, the very image of parricide, while for Breton, they are just depressing, reminding him of his literary forebears.

"The 'whom do I haunt?' posed by Breton at the beginning of the book is revealed as Breton's melancholic

"The 'whom do I haunt?' posed by Breton at the beginning of the book is revealed as Breton's melancholic

trawl of the patchwork of paternal literary figures

(Rousseau, Nerval, Baudelaire etc.) emerging in Nadja

as the 'primordial' signifiers that make up his Paris.

Breton buries himself in relations to these signifiers as

he delves into a bit of Nadja's psychosis. His fleeting

interest in Nadja is as link to that lost literary history"

See how the same image can bring about different responses? A realist interpretation would never have explained them. Surrealism brings to the images the powerful contribution of the unconscious. Internal feeling is as real as the material reality out there.

'Nadja' is very important for the History of Photography, because it introduces the concept of shifting signifiers - there's not a one-to-one correspondance with what the image apparently depicts.

Realism, the earlier paradigm of photography, is therefore inadequate.

Although Breton died in 1966, Surrealism continued to exercise its influence up to the 1970s, notably in the work of women photographers, such as Diane Arbus, Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman - who mentions explicitly 'Nadja' among her influences.

With her performances and body art photographs Francesca Woodman showed how women can reappropriate their own bodies, by turning upside down the male imaginary.

*

'Nadja' is very important for the History of Photography, because it introduces the concept of shifting signifiers - there's not a one-to-one correspondance with what the image apparently depicts.

Realism, the earlier paradigm of photography, is therefore inadequate.

Although Breton died in 1966, Surrealism continued to exercise its influence up to the 1970s, notably in the work of women photographers, such as Diane Arbus, Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman - who mentions explicitly 'Nadja' among her influences.

With her performances and body art photographs Francesca Woodman showed how women can reappropriate their own bodies, by turning upside down the male imaginary.

*

And now, just to lighten up, another photo from my friend Jouanisson on American Realism:

No Photo is innocent! We will soon discuss what happened to photography at the era of the internet globalization. When everything went to the dogs with a surfeit of special effects, allowed by the advent of digital. And when millions of digital images pushed aside what had been the little world of the paper image.

Stay tuned!

Stay tuned!